For Science 🔭#

Why I Choose to Use Python 🐍 for Science 🔭

Story#

From Childhood to Code#

As a child, I began my journey into programming by developing software in VB6 and Delphi 7-Xe2. It was a thrilling hobby, allowing me to create GUI applications with ease and develop great softwares using these tools. However, these environments had their downsides. They often masked underlying complexities, and I didn’t learn much about algorithms or data structures. I was simply translating my ideas into code without truly understanding the mechanics. This approach wasn’t conducive to performance or a deep understanding of how things work. Learning C/C++ felt like a chore because it wasn’t as gratifying; development was slow, and the programs often looked ugly (console).

From Hobbies to Studies#

My academic journey led me to study Physics and Chemistry. Here, I delved into understanding how things work, from the basics of transistors to the principles of physics—what our ancient ancestors called « nature. » As I gained more confidence in my knowledge, I dabbled in Assembly 86x64 with AVX2, C, and C++. Despite my efforts to find the perfect programming language, success eluded me. Becoming a first-class developer requires an intimate understanding of architecture and more. Creating a Software as a Service (SaaS) with a Python backend and a JavaScript frontend doesn’t demand top-tier performance, but that isn’t my goal.

The Quest for Practicality#

My goal is to use my computer to solve physics problems and create small simulations and tools for my students. Python emerged as the ideal choice for this purpose. It’s versatile, easy to learn, and supported by a vast ecosystem of libraries suited for scientific computing. Python allows me to efficiently translate complex scientific concepts into code, providing a balance between ease of use and powerful capabilities.

Another small benchmark#

In this brief article, I want to illustrate the ease or difficulty of using common libraries and explain why I have decided to abandon C++ for my teaching activities as a physics teacher.

The bench#

For instance, consider the task of multiplying two 3000x3000 matrices, a common problem in scientific computing. In Python, using libraries like NumPy, this task becomes straightforward and efficient. See how this task is done in C++.

Beginner approach#

Python with Numpy#

import numpy as np

import time

# Create large matrices

a = np.random.rand(3000, 3000)

b = np.random.rand(3000, 3000)

# Time the matrix multiplication

start = time.time()

c = np.dot(a, b)

end = time.time()

print(f"Time taken by NumPy: {end - start} seconds")

Astuce

Results for Python / Numpy : 0.1469 seconds

C++ - Naïve - MSVC#

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.28)

project(Simple)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 17)

# Add optimization flags for Release build type

set(CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE} /O2 /Ox")

add_executable(Simple main.cpp)

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <chrono>

void matmul(const std::vector<std::vector<double>>& A,

const std::vector<std::vector<double>>& B,

std::vector<std::vector<double>>& C) {

int n = A.size();

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

C[i][j] = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < n; ++k) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

}

int main() {

int n = 3000;

std::vector<std::vector<double>> A(n, std::vector<double>(n));

std::vector<std::vector<double>> B(n, std::vector<double>(n));

std::vector<std::vector<double>> C(n, std::vector<double>(n));

// Initialize matrices

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

A[i][j] = rand() / double(RAND_MAX);

B[i][j] = rand() / double(RAND_MAX);

}

}

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

matmul(A, B, C);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> duration = end - start;

std::cout << "Time taken by C++: " << duration.count() << " seconds" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Astuce

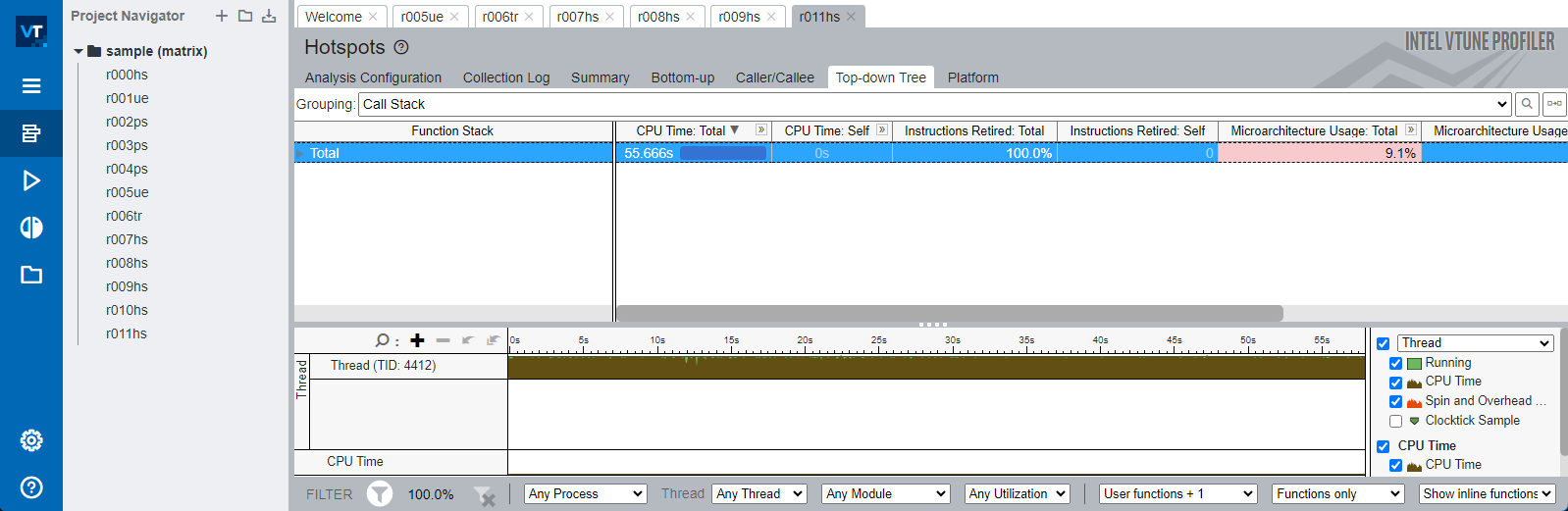

Results for C++ / Naïve : 55.9159 seconds

How to explain the differences between the two ?#

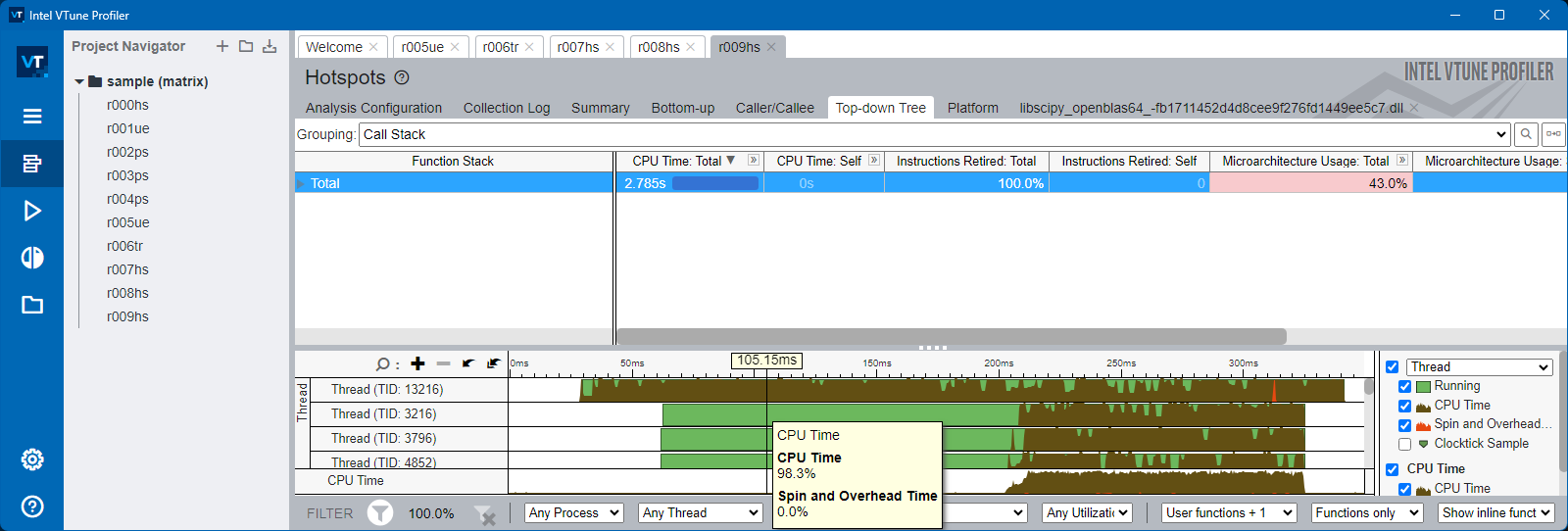

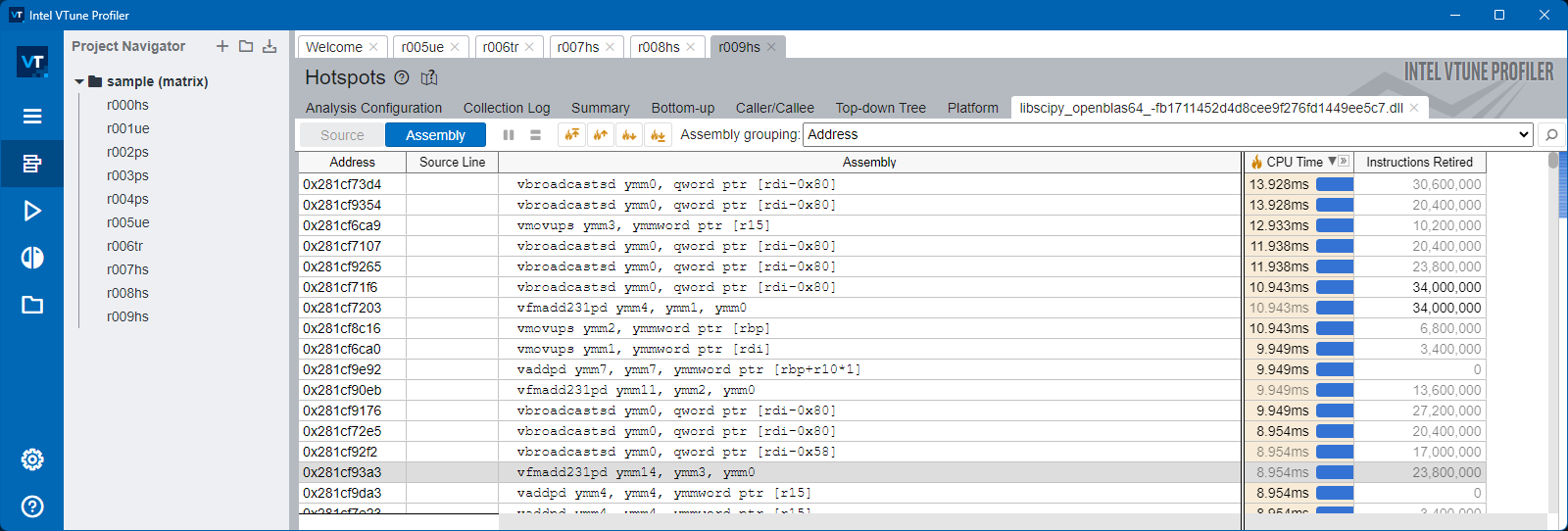

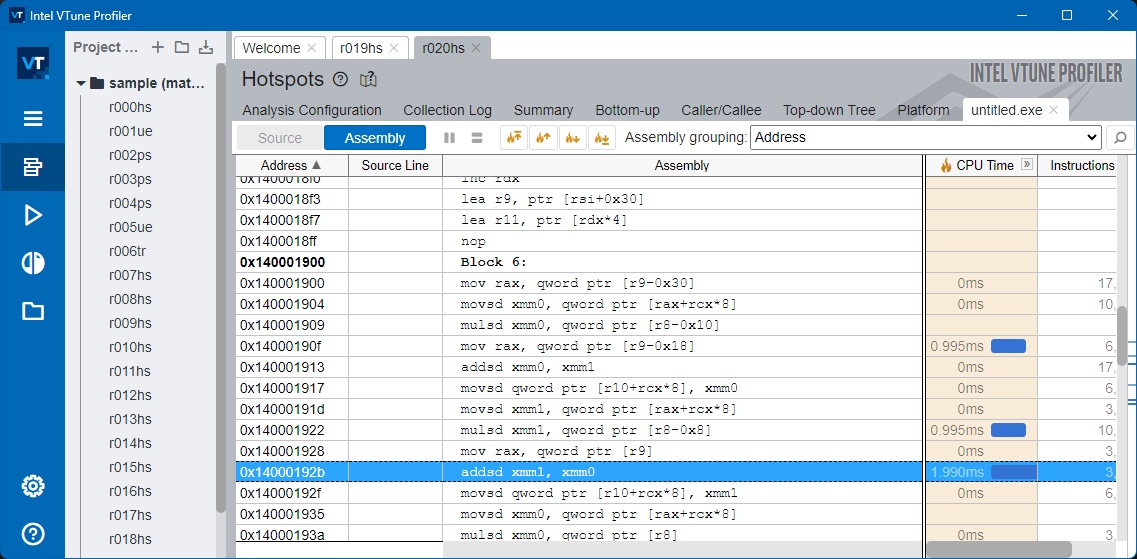

To inspect and study this, we will use Intel VTune profiler

Numpy#

C++ - MSVC#

Danger

My Naïve version isn’t using AVX2 but SSE instruction set and isn’t multithreaded

Improving the C++ program#

AVX2 and Multithreading with OpenMP#

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.28)

project(SimpleAVX2MP)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 17)

# Add optimization flags for Release build type

if (MSVC)

set(CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE} /O2 /Ox /Arch:AVX2")

endif()

# Find OpenMP

find_package(OpenMP REQUIRED)

add_executable(SimpleAVX2MP main.cpp)

# Link OpenMP libraries

if(OpenMP_CXX_FOUND)

target_link_libraries(SimpleAVX2MP PUBLIC OpenMP::OpenMP_CXX)

endif()

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <chrono>

#include <omp.h>

void matmul(const std::vector<std::vector<double>>& A,

const std::vector<std::vector<double>>& B,

std::vector<std::vector<double>>& C) {

int n = A.size();

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

C[i][j] = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < n; ++k) {

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

}

int main() {

int n = 3000;

std::vector<std::vector<double>> A(n, std::vector<double>(n));

std::vector<std::vector<double>> B(n, std::vector<double>(n));

std::vector<std::vector<double>> C(n, std::vector<double>(n));

// Initialize matrices

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (int j = 0; j < n; ++j) {

A[i][j] = rand() / double(RAND_MAX);

B[i][j] = rand() / double(RAND_MAX);

}

}

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

matmul(A, B, C);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> duration = end - start;

std::cout << "Time taken by C++: " << duration.count() << " seconds" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Astuce

Results for C++ / OpenMP / AVX2 : 7.4244 seconds

Using a specialized library like Eigen#

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.28)

project(EigenOpenMPAVX2)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 17)

# Add optimization flags for Release build type

set(CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE} /O2 /Ox /Ob3 /arch:AVX2")

find_package(OpenMP REQUIRED)

# Add the path to the Eigen directory

set(EIGEN3_INCLUDE_DIR "C:/Users/remi/CLionProjects/untitled1/eigen")

# Include the Eigen directory

include_directories(${EIGEN3_INCLUDE_DIR})

add_executable(EigenOpenMPAVX2 main.cpp)

if(OpenMP_CXX_FOUND)

target_link_libraries(EigenOpenMPAVX2 PUBLIC OpenMP::OpenMP_CXX)

add_definitions(-DEIGEN_USE_THREADS)

endif()

#include <iostream>

#include <Eigen/Dense>

#include <chrono>

#include <omp.h>

int main() {

int n = 3000;

Eigen::MatrixXd A = Eigen::MatrixXd::Random(n, n);

Eigen::MatrixXd B = Eigen::MatrixXd::Random(n, n);

Eigen::MatrixXd C(n, n);

//Set the number of threads for OpenMP

int num_threads = omp_get_max_threads();

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

Eigen::setNbThreads(num_threads);

std::cout << "Using " << num_threads << " threads for Eigen." << std::endl;

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

C.noalias() = A * B; // Use noalias to avoid temporary allocation

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> duration = end - start;

std::cout << "Time taken by Eigen with OpenMP: " << duration.count() << " seconds" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Astuce

Results for C++ / OpenMP / AVX2 / Eigen : 0.2219 seconds

It’s better but not as a fresh install of numpy (10 seconds to install it)

Using OpenBLAS with MinGW#

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.15)

project(OpenBLASExample)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 14)

# Define the path to your OpenBLAS installation

set(OpenBLAS_DIR "C:/Users/remi/CLionProjects/obl/openblas")

# Add the OpenBLAS include and library directories

include_directories(${OpenBLAS_DIR}/include)

link_directories(${OpenBLAS_DIR}/lib)

# Add an executable (replace main.cpp with your source file)

add_executable(OpenBLASExample main.cpp)

# Set compiler optimization flags

set(COMPILER_OPT_FLAGS "-O3 -march=native -flto -fopenmp")

# Link OpenBLAS library

target_link_libraries(OpenBLASExample ${OpenBLAS_DIR}/lib/libopenblas.a)

#include <cblas.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

int main() {

const int size = 3000;

double *A = new double[size * size];

double *B = new double[size * size];

double *C = new double[size * size];

for (int i = 0; i < size * size; ++i) {

A[i] = rand() / double(RAND_MAX);

B[i] = rand() / double(RAND_MAX);

}

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

cblas_dgemm(CblasRowMajor, CblasNoTrans, CblasNoTrans, size, size, size, 1.0, A, size, B, size, 0.0, C, size);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> diff = end - start;

std::cout << "Time to multiply matrices with OpenBLAS: " << diff.count() << " s\n";

delete[] A;

delete[] B;

delete[] C;

return 0;

}

Astuce

Results for C++ / OpenMP / AVX2 / OpenBLAS : 0.1496 s

Using Intel Math Kernel Library#

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.28)

project(MKLProject)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 17)

# Add optimization flags for Release build type

set(CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE "${CMAKE_CXX_FLAGS_RELEASE} /O2 /Ox /Ob3 /arch:AVX2")

include_directories("C:/Program Files (x86)/Intel/oneAPI/compiler/2024.2/include")

link_directories("C:/Program Files (x86)/Intel/oneAPI/compiler/2024.2/lib")

# Include the MKL directories (adjust these paths according to your MKL installation)

include_directories("C:/Program Files (x86)/Intel/oneAPI/mkl/2024.2/include")

link_directories("C:/Program Files (x86)/Intel/oneAPI/mkl/2024.2/lib")

# Add executable

add_executable(MKLProject main.cpp)

# Link the MKL libraries

target_link_libraries(MKLProject PUBLIC mkl_intel_lp64 mkl_intel_thread mkl_core libiomp5md)

#include <iostream>

#include <chrono>

#include <mkl.h>

int main() {

int n = 3000;

// Allocate matrices

double* A = new double[n * n];

double* B = new double[n * n];

double* C = new double[n * n];

// Initialize matrices A and B with random values

for (int i = 0; i < n * n; ++i) {

A[i] = static_cast<double>(rand()) / RAND_MAX;

B[i] = static_cast<double>(rand()) / RAND_MAX;

C[i] = 0.0;

}

// Set the number of threads for MKL

int num_threads = mkl_get_max_threads();

mkl_set_num_threads(num_threads);

std::cout << "Using " << num_threads << " threads for MKL." << std::endl;

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

// Perform matrix multiplication using MKL's dgemm function

cblas_dgemm(CblasRowMajor, CblasNoTrans, CblasNoTrans, n, n, n, 1.0, A, n, B, n, 0.0, C, n);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> duration = end - start;

std::cout << "Time taken by MKL for matrix multiplication: " << duration.count() << " seconds" << std::endl;

// Clean up

delete[] A;

delete[] B;

delete[] C;

return 0;

}

Astuce

Results for C++ / Intel MKL : 0.1111 seconds

Working with Cython#

Naïve version#

from setuptools import setup

from Cython.Build import cythonize

setup(

ext_modules = cythonize("matrix_multiply.pyx")

)

import cython

from libc.stdlib cimport malloc, free, rand, RAND_MAX

from libc.time cimport clock, CLOCKS_PER_SEC

@cython.boundscheck(False)

@cython.wraparound(False)

cdef void matmul(double** A, double** B, double** C, int n):

cdef int i, j, k

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

C[i][j] = 0

for k in range(n):

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]

def matrix_multiply(int n):

cdef int i, j

cdef double** A = <double**>malloc(n * sizeof(double*))

cdef double** B = <double**>malloc(n * sizeof(double*))

cdef double** C = <double**>malloc(n * sizeof(double*))

cdef double start, end

for i in range(n):

A[i] = <double*>malloc(n * sizeof(double))

B[i] = <double*>malloc(n * sizeof(double))

C[i] = <double*>malloc(n * sizeof(double))

# Initialize matrices

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

A[i][j] = rand() / RAND_MAX

B[i][j] = rand() / RAND_MAX

start = clock()

matmul(A, B, C, n)

end = clock()

# Free allocated memory

for i in range(n):

free(A[i])

free(B[i])

free(C[i])

free(A)

free(B)

free(C)

return (end - start) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC

Astuce

Results for Cython : 60.487 seconds

With small optimization#

from setuptools import setup, Extension

from Cython.Distutils import build_ext

ext_modules = [

Extension(

'matrix_multiply2',

sources=['matrix_multiply2.pyx'],

extra_compile_args=['/openmp', '/O2','/arch:AVX2'] # Enable OpenMP and AVX2

)

]

setup(

name='matrix_multiply2',

ext_modules=ext_modules,

cmdclass={'build_ext': build_ext},

)

import cython

from libc.stdlib cimport malloc, free, rand, RAND_MAX

from libc.time cimport clock, CLOCKS_PER_SEC

from cython.parallel cimport prange, parallel

@cython.boundscheck(False)

@cython.wraparound(False)

cdef void matmul(double** A, double** B, double** C, int n):

cdef int i, j, k

# Use OpenMP to parallelize the outer loop

for i in prange(n, nogil=True,num_threads=16):

for j in range(n):

C[i][j] = 0

for k in range(n):

C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]

def matrix_multiply(int n):

cdef int i, j

cdef double** A = <double**>malloc(n * sizeof(double*))

cdef double** B = <double**>malloc(n * sizeof(double*))

cdef double** C = <double**>malloc(n * sizeof(double*))

cdef double start, end

for i in range(n):

A[i] = <double*>malloc(n * sizeof(double))

B[i] = <double*>malloc(n * sizeof(double))

C[i] = <double*>malloc(n * sizeof(double))

# Initialize matrices

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

A[i][j] = rand() / RAND_MAX

B[i][j] = rand() / RAND_MAX

start = clock()

matmul(A, B, C, n)

end = clock()

# Free allocated memory

for i in range(n):

free(A[i])

free(B[i])

free(C[i])

free(A)

free(B)

free(C)

return (end - start) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC

Astuce

Results for Cython / OpenMP / AVX2 : 7.363 seconds

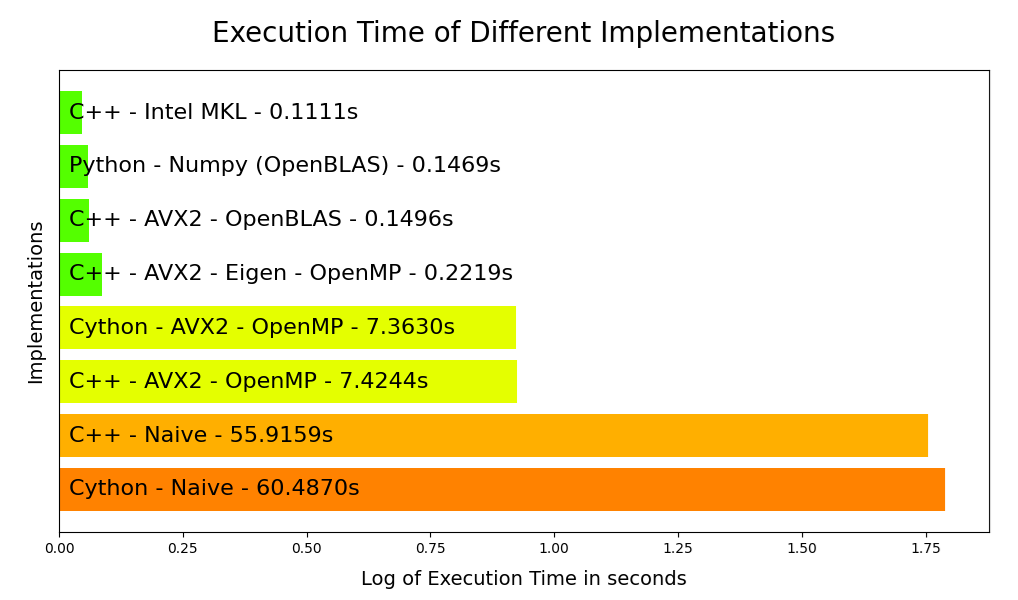

Benchmark results#

So to recap :

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.colors as mcolors

# Data

languages = ['Cython - Naive', 'C++ - Naive', 'C++ - AVX2 - OpenMP', 'Cython - AVX2 - OpenMP',

'C++ - AVX2 - Eigen - OpenMP', 'C++ - AVX2 - OpenBLAS', 'Python - Numpy (OpenBLAS)', 'C++ - Intel MKL']

r_times = [60.487, 55.9159, 7.4244, 7.363, 0.2219, 0.1496, 0.1469, 0.1111]

times = [time + 1 for time in r_times]

times

log_times = np.log10(times)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

# Combine language names and times for the labels

labels = [f'{lang} - {time:.4f}s' for lang, time in zip(languages, r_times)]

# Create a colormap from red to blue

cmap = plt.get_cmap('prism_r')

norm = mcolors.Normalize(vmin=min(r_times), vmax=max(r_times))

colors = [cmap(norm(time)) for time in log_times]

# Create horizontal bar chart

bars = plt.barh(range(len(languages)), log_times, color=colors)

# Set the global font size to 14

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 14})

# Add text labels on the bars

for bar, label in zip(bars, labels):

plt.text(0.02, bar.get_y() + bar.get_height() / 2, label, va='center', ha='left', color='black', fontsize=16)

# Remove y-axis labels

plt.yticks([])

plt.xlabel('Log of Execution Time in seconds', fontsize=14, labelpad=10)

plt.ylabel('Implementations', fontsize=14, labelpad=10)

plt.title('Execution Time of Different Implementations', pad=20, fontsize=20)

plt.show()

Conclusion#

Clearly, the three lines of code for Numpy are unbeatable. Within a minute, I achieve performance levels that surpass anything I can produce in C++ (except when using Intel MKL, which is a proprietary library).

C++ allows for complete, meticulous control over what you execute on the processor. However, using a library like OpenBLAS or Intel MKL is akin to using a black box, just like Numpy.

Talented scientists and engineers have worked on these libraries. Why reinvent the wheel? Why start from scratch as a scientist?

Python is the perfect tool because it is simple and intuitive for teaching physics. Its performance, when used correctly (with compiled libraries for critical parts), is more than sufficient for any university professor, at least up to a Master’s level.